With each passing day, new technologies crop up and become integral parts of our social media-entrenched, smart device-embedded lives. When we use these new technologies, we trade access to our intimate moments for convenience and entertainment.

The petabytes of data generated by each waking (and sleeping!) nanosecond are a treasure trove for the companies that make the apps, and for researchers that use the data to see patterns in our collective intimate moments. The potential benefits are astounding, but this new data can sometimes mislead researchers into thinking they have a better view than they actually do, particularly for marginalized communities.

In this piece I explore how the big data generated by social media is informing – or misinforming – research initiatives and impact evaluation in the social sector.

The Pros

Big data from social media platforms have yielded some significant research insights in recent years. A few highlights include:

- The ability to predict which peer-reviewed articles will be highly cited within the first 3 days of article publication based on Twitter activity.

- New hypotheses about psychosocial processes thanks to the text analysis of 700 million words from the Facebook messages of 75,000 volunteers (the largest study of language and personality).

- New ways to visualize and explore social dynamics and hierarchies in urban spaces thanks to the application of network analysis on geotagged Instagram posts from Amsterdam and Copenhagen.

- Opportunities for the rapid assessment and relief of disasters through real-time monitoring of environmental, social and geopolitical events as demonstrated by the strong correlation between Twitter activity and damage before, during, and after Hurricane Sandy.

- The potential to identify patterns in youth drinking through the image & text analysis of Instagram posts.

- New ways to keep our politicians accountable as demonstrated by the coupling of Instagram data and public flight manifests to expose IL congressman Schock’s misuse of taxpayer money. (He resigned!)

The Cons

As our data warehouses fill with an ever-increasing backlog of unanalyzed information, we must remember that all this data is being generated only by people with smartphones, and with an interest in these specific issues and technologies. Just because the data is big doesn’t mean it’s at all representative of society.

This is especially important to understand when business, political, and public policy decisions are made based on the findings. The particulars of a city’s demographics coupled with the platform in question, converge to render different populations (in)visible and it is important to explore and understand these blind spots in order to prevent misguided decisions.

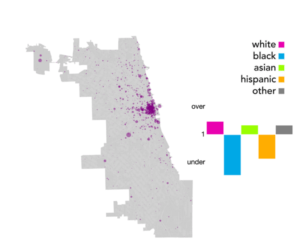

For instance, consider Chicago’s Instagram presence. Studies analyzing the activity of Instagram users have yielded skewed results that do not reflect the true racial demographics of the city. Black populations are so underrepresented on Instagram that they would have to to more than double their participation rates (and Hispanic populations would have to nearly double theirs) in order to be represented on Instagram in the same proportion as they are in the community.

Meanwhile, white and Asian populations are overrepresented on Instagram. Now imagine if intervention programs were put in place to combat youth drinking based on the behavior patterns of only the subset of Chicagoans captured by this data. Would the intervention strategies generalize to all youth, or would the particular characteristics of different subcultures and status hierarchies limit their impact?

Racial Representation in Chicago’s Instagram

The Takeaway

Don’t assume that big data is comprehensive data. Demographic groups that tend to be marginalized also tend to have less of a social media presence. Researchers must acknowledge and mitigate the skewed demographics of social media data in their analyses of social trends. By taking a critical look at these data we can avoid drawing misguided conclusions or designing ineffective solutions based on what many consider to be “objective” data.

Does your organization use social media data to understand social problems or measure impact? How do you control for potential bias in these data? Chime in with a comment below. You can also connect with Jess Freaner on Twitter or LinkedIn. Learn more about Datascope Analytics on their website.

To stay up to date with the latest from Markets For Good, sign up for our newsletter and follow us on Twitter. Better yet, become a contributor!