A new concept brief outlines a framework for data responsibility as practice and culture among humanitarian organizations.

Citing the rise of digital data use in humanitarian action, a think piece developed under the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) calls for a “humanitarian data-ecosystem” firmly rooted in a shared culture of data responsibility.

“Because affected populations can be harmed as well as helped by the use of data,” the authors write, “frameworks must be established to ensure that humanitarians understand and mitigate risks caused by the use of data.”

Produced through the Policy Development and Studies Branch of OCHA, Building Data Responsibility into Humanitarian Action is not a formal policy paper but a thought piece designed to propose ideas and spur constructive feedback on an increasingly important issue: how to use data to support humanitarian responses in ways that are not only effective but safe, ethical, and holistic in their approach.

The authors describe the “humanitarian data ecosystem” as the network of humanitarian organizations, affiliates, and affected communities who are producing, consuming, collecting, and analyzing digital data, including “mobile phone records, social media posts, satellite imagery, sensor data, financial transactions,” and more.

As the authors note, such data has profound potential for supporting humanitarian response efforts. Among recent “success cases” was an effective effort to use mobile phone data to track and extend support to displaced populations in Nepal following the earthquake in 2015.

Yet the authors also cite the 2015 Ebola crisis in West Africa as an example of how efforts to collect and use data for a humanitarian response actually exposed the affected population to greater risk: “Attempts to use anonymized CDRs and other types of data to track the spread of the virus failed due to the lack of privacy protection standards, guidelines, data sharing mechanisms, and anonymization techniques.”

Such cases point to the array of challenges that humanitarian agencies face in terms of properly generating, collecting, securing, anonymizing, sharing, and analyzing data, particularly in the fluid, unstructured, and time-sensitive contexts of humanitarian crises and disasters.

To address these concerns, the authors propose a four-step process as a “practical guide” for ensuring data responsibility for humanitarian action in the field:

- Evaluating the context and purpose within which data is being generated and shared

- Taking inventory of the data and how it is stored

- Pre-identifying risks and harms associated with a proposed use of data before data is collected

- Developing strategies to mitigate those risks.

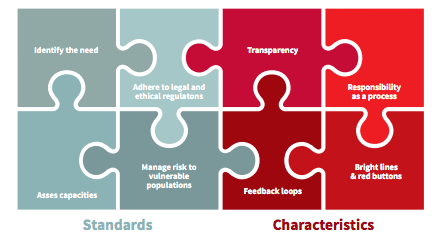

The authors call for this process to be embedded within a larger framework of data responsibility to be developed and adopted across the humanitarian sector. They suggest four baseline standards for such a framework: “identifying need, assessing core competencies and capacities, managing risk to vulnerable populations, and ensuring adherence to legal and ethical regulations.”

Source: Building Data Responsibility into Humanitarian Action, OCHA Policy and Development Studies Branch

For the framework to be effectively implemented, the authors propose that humanitarian organizations each adopt the following “characteristics” as part of their policies, procedures, and culture: “responsibility as a process”; “‘bright line’ rules and ‘red-button’ responses” (restrictions and policies on data use and emergency cessation of projects); “transparency”; and “feedback loops.”

The desired outcome would be a sector-wide practice and culture of data responsibility that extends beyond “data privacy” and “data protection” to include a comprehensive and coordinated approach to risk mitigation.

The authors assert that a culture of collective responsibility will be the key to ensuring the safe, ethical, and effective use of data for humanitarian response:

Importantly, participants in the humanitarian data ecosystem will need to look beyond their own organization to ensure that their broader environment is adhering to the principles and practices of humanitarian data responsibility. Without a holistic, ecosystem-wide approach, humanitarian data use will only be as responsible as the weakest link in the data chain.

The authors of the think brief are Nathaniel Raymond and Ziad Al Achkar, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative; Stefaan Verhulst, The GovLab, NYU Tandon School of Engineering; and Jos Berens, Leiden University Centre for Innovation.