Rhode Island-based cartographer Jeffrey Yoo Warren understands the value of smartphone location-sharing—whether for detecting pollution from a nearby industrial site, connecting with singles, or monitoring a pandemic. But Warren sees the myriad issues around privacy the practice raises. Like many others, he’s concerned about the hundreds and even thousands of times a day his smartphone is tracked and how the practice could affect the privacy and physical safety of others.

As an advocate for environmental justice, Warren questions the “all-or-nothing” approach tech developers take—and consumers accept—when it comes to tracking cellphone pings.

“When people download an app, they tend to think they have to give up their privacy in return for getting location services or they won’t get those services at all,” says Warren. “Because technology companies have been in the driver’s seat, consumers are stuck in this either/or mindset about location-sharing and privacy. It doesn’t have to be this way.”

Warren is on a mission to create a new global standard for privacy and location sharing. With support from Digital Impact, Warren and the Public Laboratory for Open Science and Technology (Public Lab) have developed an open-source tool for geographic tracking that enables smartphone users to choose how precisely their location is shared, while also giving organizations the information needed to deliver their services. Warren, who until recently served as Public Lab’s research director, continues to collaborate with the organization.

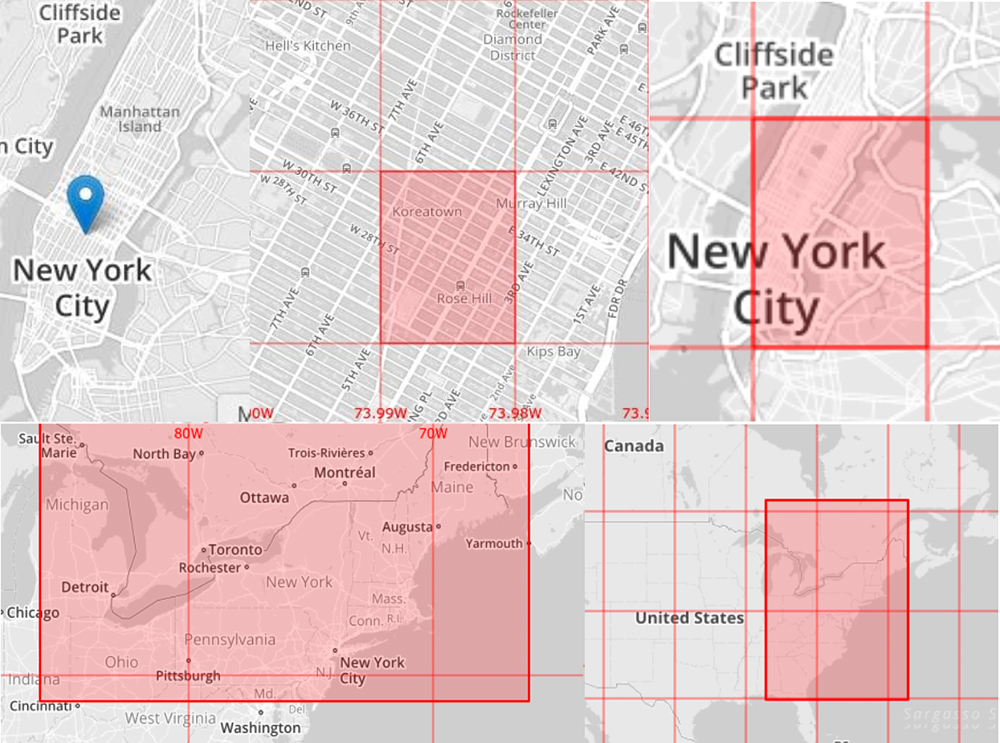

If the Community Data Privacy Toolkit is widely adopted, the smartphone notifications that ask users for their locations will look different. Users will be asked to set a level of privacy from a range of options using a zoomable map. They can agree to reveal their exact location or choose to “blur” themselves at the neighborhood, county, state, or even country level (with other parameters in between).

“We’ve essentially taken the black-and-white model for location tracking and privacy and shown—in ways that are transparent and easy to use—that there can be grey zones,” Warren says.

A New Standard: Variable Location Privacy

Transparency forms a crucial part of the debate over location sharing and privacy. Location-dependent services like Airbnb and Tinder take steps to obscure where people are. Airbnb hosts, for example, can choose to show the general area of their residence before releasing the exact location to a guest once a reservation is made. Tinder relies on precise locations to connect the lovelorn within a radius of their choosing, but doesn’t show their locations as precise pins on a map.

The problem with both of these services is that they don’t share exactly how they protect their users’ privacy. “A lot of companies know how complicated location privacy is, which is why they decide to be vague about it,” says Warren. “To them, ‘kind of works’ is good enough.”’

Warren and Public Lab want the Community Data Privacy Toolkit to be transparent in its methodology but also robust enough to ensure that users are visible only to the extent they want to be.

“We can do the technology piece of this,” says Shannon Dosemagen, the executive director of Public Lab. She says that “everything else complicates” the creation of a new global standard. This includes building awareness around privacy among web developers, policymakers and others. It also means addressing a host of legal, cultural and other non-technical issues.

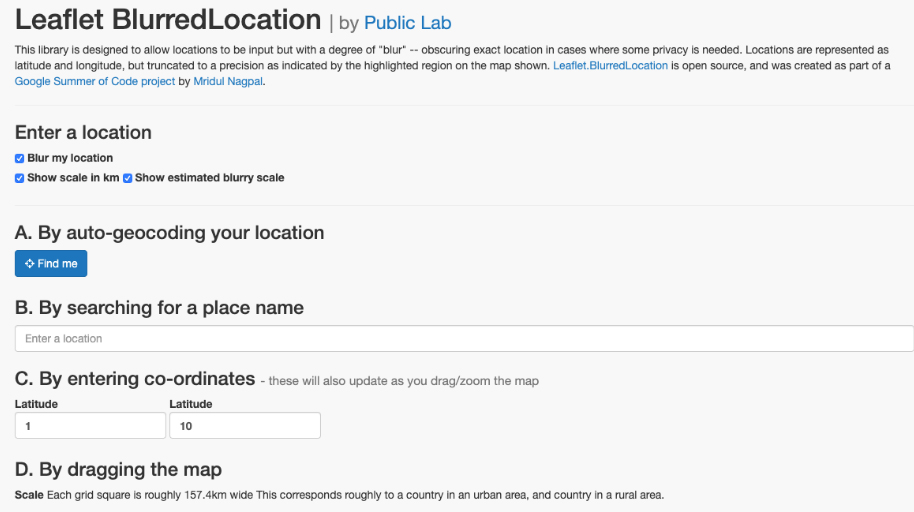

To build a prototype, Warren and his team used the open-source web mapping library Leaflet to create an interactive world map with fixed grids of varying sizes based on latitude and longitude coordinates. When accessing the tool, users see a highlighted grid depicting their location or any destination they choose. As users zoom in and out of the map, the grid squares expand and shrink accordingly. In this way, users can blur their locations depending on how much specificity they want to divulge.

For example, someone who lives in a rural area with few neighbors might choose a larger grid, while an urbanite surrounded by thousands of people might opt for a smaller grid with a narrow range of coordinates. (You can demo the tool here.)

According to Warren, the model overcomes a number of challenges with existing location-tracking technologies. For example, platforms typically insert random location data in such a way that, when repeated many times, may expose the person’s true location. But by using a fixed grid, or series of fixed grids at different decimal points, the Public Lab developers avoided the need to insert random data. Using truncated coordinates means that anyone trying to figure out an exact location would see only the boundaries of the grid square.

Warren says the “variable location privacy” method doesn’t require web developers to start from scratch. “We made very careful design choices, including to develop this in Javascript, so people don’t have to throw away their existing mapping systems. They can layer this on top of what already exists.”

A Starting Point for Developers

Creating a new framework around location privacy is ambitious, which means the prototype may not always function as intended. A recent test from a location in Berkeley, California yielded a highlighted grid that omitted the city entirely, instead depicting portions of Silicon Valley some 20 miles away. The tool has also produced “edge cases,” where someone happens to be at the corner of a grid square. If that person moves at all, he or she may cross the boundary and a neighboring grid square lights up—essentially disclosing the user’s location.

“All location-tracking methods have some drawbacks,” says Warren. “In this case, at least the user can see when the tool breaks down. Our hope is that other people will take what we’ve built and improve upon it.”

For more information, visit Public Lab’s open source toolkit and listen to our podcast with Jeffrey Warren. From 2016 to 2018, Digital Impact awarded grants to research teams looking to advance the safe, ethical, and effective use of digital resources for social good. With support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Digital Impact Grants program awarded more than half a million dollars over three years.