Beth Kanter shares her take on the infamous Ice Bucket Challenge - why did it go viral, and what can we take from it?

As of August 26, The Ice Bucket Challenge has raised over $88.5 Million Dollars to fight the horrible disease, according to the ALS Association web site. Just one week ago, donations totaled $22.6 million. In just seven days, donations have skyrocketed by an average of $9 million per day, now totaling $88.5 million. Click the image below for further facts behind the challenge.

And critics, with a scarcity mindset, talk about slacktivism (“Not everyone who did the challenge donated or even mentioned ALS”) and fundraising cannibalism (“People won’t donate to other charities because they will be tapped out”). Nonprofit insiders are watching and debating how ALS will use the money and the donor retention strategy. And, of course the valid concern of wasting water in a drought.

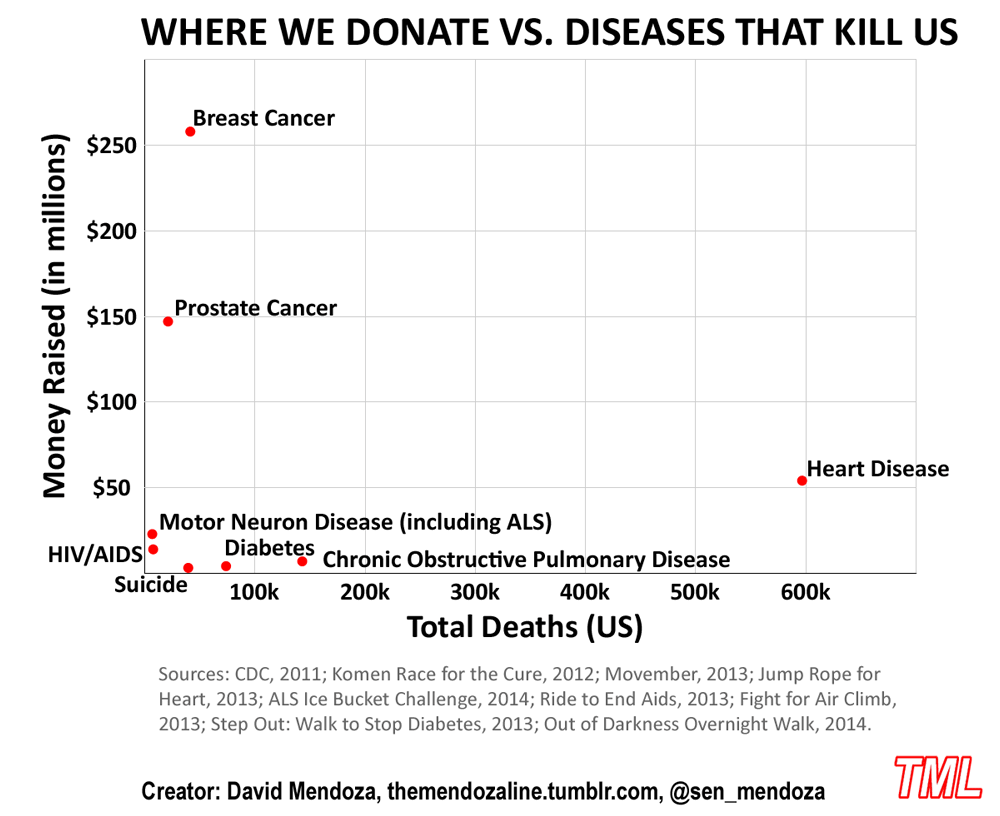

And if you did an analysis of money raised for specific diseases by the number of deaths, you can see that cancer raises more money than other diseases. But heart disease has 10x more deaths.

One has to step back and marvel at the most successful networked fundraising campaigns in the history of social or crowd fundraising. The numbers speak for themselves.

When Allison Fine and I wrote the Networked Nonprofit we were talking about how nonprofits needed to work less like isolated institutions and more like networks, considering the “crowds,” people inside and outside their organizations and other similar nonprofits as valuable to their work. We are in the collaborative economy or sharing economy – and we now have “crowd companies.” Why not “crowd nonprofits” that share program delivery, administration, and fundraising. The question on my mind is: Is the success of the Ice Bucket Challenge a happy accident for ALS fundraising and the people who suffer from the disease or is the first example of the power of crowd charity?

Let’s look at the possible factors that caused philanthropy to run wild and capture the attention of so many people, inspire them to participate, and donate to stop the disease. What can or cannot be reproduced?

(1) Downer News Cycle: Last week, in an interview with NPR, I pointed to the long cycle of bad news we had experienced over the summer as one possible reason the Ice Bucket Challenge had so much appeal. In deck above, you will see a graph that shows that the Ice Bucket Challenge had more search volume than other news such as Ferguson and Iraq during the last few weeks. This shows the importance of timing and playing off current events. It goes beyond what is known as “newsjacking,” to analyze public reaction and also have the agility to strike while the iron is hot.

(2) Playing on Memes: The campaign took advantage of social media narcissism for a good cause. But unlike other campaigns where the idea to incorporate a meme was part of a campaign organized by an organization or central entity (for example, Giving Tuesday’s “UnSelfie Campaign“), the fundraiser itself was a meme that went viral, not only as a fundraiser, but its own Internet meme (see this Star Wars version and others). The ice bucket challenge has been going on for a while now among golfers and many others donating to the charity of their choice but did not really spread until Pete Frates, the former captain of Boston College’s baseball team, re-purposed the meme by challenging Steve Gleason to throw a bucket of ice over his head to raise awareness for ALS. (You can see how it spread from Massachusetts to the rest of the country via this Facebook data)

(3) Influencers: Pete Frates was one of the early “influencers” or what Allison Fine and I called “Free Agents,” people who have large and passionate networks that they can leverage for a good cause. But he had help from another free agent, Corey Griffen, a management consultant who organized the fundraiser. Sadly, Griffen, died in a drowning accident on August 16th. Reaching out to and cultivating people with large networks who are passionate about your cause is something your nonprofit can reproduce and should do. But the fundraiser meme went beyond the sports world, when hundreds of celebrities (or their PR agents) picked up on the idea. Celebrities and fundraisers are nothing new and even having a critical mass of celebrities join forces for a good cause is not new (think Bob Geldof and LiveAid). But, there was not a central coordinating organization or purpose for this celebrity participation, it was self-organizing. So, just because your nonprofit may get one celebrity to join your fundraiser, it won’t create a cascade of sand of others joining in without even being asked.

(4) PhilanthroKids and Philanthropy Education: We are seeing the rise of PhilanthroKids, as GenZ starts to use the technologies for good causes. As more kids are heading back to school, teachers and whole schools are embracing the challenge and teaching some important lessons about philanthropy. Vickie Davis of CoolCatTeacher Blog let her students dump water on her and then taught them a lesson on fundraising for a good cause and about ALS. Involving younger people in your organization’s campaigns, as champions, perhaps as part of a lesson on philanthropy is definitely something that can be replicated in other campaigns.

(5) Whacky, Goofy, and Fun: “Stunt Philanthropy” has been around for years. It is a combination of public dare combined with something outrageous. In the early days of social fundraising, individuals challenge their networks to donate and they would do something crazy in response – like shave their head, sing a Beyonce song, or dress up like giant tomato and walk down 42nd street. I chronicled some of these back in 2008. But the top wild fundraisers by organizations have raised only a small percentage of what the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge has raised so far – so if your nonprofit embraces stunts, be sure to adjust your expectations and take advantage of social proofing. Also, make sure your stunt won’t cause a backlash and is appropriate to the timing of your campaign. Ice Bucket Challenge in winter time would not have worked.

(6) Social Proofing the Call To Action: Another reason is the social proofing element or social validation, where friends tag their friends on social network. Social proof is peer pressure in a positive way, the positive influence created when people find out others are doing something – now, suddenly, everyone else wants to do that something too. Social proofing or tagging your call to donate is something that be replicated.

Summary

As you can see, some aspects of the Ice Bucket Challenge can’t be replicated. Most likely, no matter how your nonprofit incorporates some of the best practices, you probably won’t raise $100 million and get hundreds of celebrities to participate on their own. But you can certainly incorporate some of the best practices like social proofing, fun call to action, and embracing free agents to get better results.

Many thanks to Beth for a fascinating look into the Ice Bucket Challenge and why it has been such a remarkable campaign. Be sure to check out her blog for alternative angles on the challenge, and as ever, follow her on Twitter.

To stay up to date with the latest Markets For Good articles and news, sign up to our newsletter here. Make sure that you are also following us on Twitter.