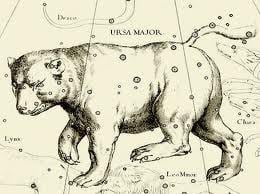

The momentum toward better use and sharing of data is clear. But, before simply continuing the march forward, Katya Smyth suggests that we adjust the lens through which we see social problems (how we see “the bear”) and then take a hard look at our base assumptions. Part I of II

Long before light pollution, some folks looked to the heavens, saw a couple of stars in a weird jumble and pronounced, “That’s a bear, and a Big Bear at that.”

Personally, I can’t see the bear unless I’m shown artfully drawn pictures, or unless a lot of little, less bright (and obvious) stars are included in the drawing. Most of the bright ones seem to be on its ribs—an odd place to start. So the bear was hard for people to see, and people drew the bear differently each time. It was mushy and not objective.

This is a lot like how we have approached data.

In the absence of any data, we didn’t know what we were looking at. So we began to collect data, such as how many people visited our food pantry each week, or how many bed-nights our shelter had, or how many 12-step meetings people attended. And these data left us with, well, the bright stars of a Big Bear—meaning data that didn’t actually paint a picture of what it was we wanted to know.

So we had to explain to people all sorts of things that required leaps of faith, such as how the number of people visiting our food pantry was somehow tied to decreased youth violence. And we’d tell a lot of stories that helped connect the dots in ways that fit our understanding of the world. We were drawing a Big Bear.

Then we began to collect more data to make our picture more complete. It was like looking through a telescope and finding the stars that, even though fainter, actually do a better job of outlining that Big Bear. As a result, we relied on fewer and fewer stories, leaps of faith, illustrated pictures, and myths to convince us that it was, indeed, a bear.

The more data we collect to outline the Big Bear, the easier it is for everyone to see what the real issues are and the less those original stars determine our interpretation. And these data, perhaps a little harder to discover at first (like the slightly fainter stars) are a lot closer to what we should track to evaluate our programs, track our outcomes, or paint real pictures of what we’re doing and what effect we are having.

After a while, we can see this sum of big and little stars and then all agree: we have a Big Bear. And once we’ve decided this, we can begin to really dig into the very important business of collecting our data in a standardized way, mining it, analyzing it.

Looking beyond the obvious gives us the clearest picture of what’s going on and whether what we are doing is working: these are vital dimensions for us to know.

That said, I also believe that there’s an astounding presumption under all of this: that what we need data for is to draw and study a bear. Because the Big Bear is how we define success for people. We—policy makers, funders, researchers, advocates, programs—do it more and more, the more focused on outcomes and data we become.

I’m not here to say the Big Bear is wrong. I just don’t know whether we check enough that it is right.

Isn’t it possible that assumptions about success that are baked into systems and services and funding, assumptions which aren’t necessarily wrong but aren’t necessarily right either, confound the best efforts to make things better?

Before we gather, share and mine data, we need to ask some more fundamental questions about how people experiencing issues understand success and transformation. This is the step before a theory of change or a theory of the problem.

It is the step that asks, “How do people who are or have been homeless understand their lives and situations and what it means to be successful and thrive? What of survivors of domestic violence? What if it’s not all defined though a prism of housing or a lack of violence?”

In Part II, on October 11, Katya expands on this view and what it means for how define success when addressing social problems.