"Based on field research and the results of a data policy survey, we knew we had to make the Guidelines practical and concrete in order to have an impact."

As OCHA and its partners process increasingly large volumes of data, we also face more complex challenges related to assessing and managing data risk. Many organizations have developed policies focused on personal data, but guidance on the management of other forms of sensitive data has been lacking. The Working Draft of the OCHA Data Responsibility Guidelines (‘the Guidelines’) aim to help fill this gap.

A main objective of the Guidelines is to help staff better assess and manage the sensitivity of the data they handle in different crisis contexts. View the PDF.

Over the next six months, we will test the Guidelines with a number of OCHA offices to see how they work in practice and identify areas for revision. We will also continue consulting with partners to see how we can further align the Guidelines with other prominent policy and guidance frameworks.

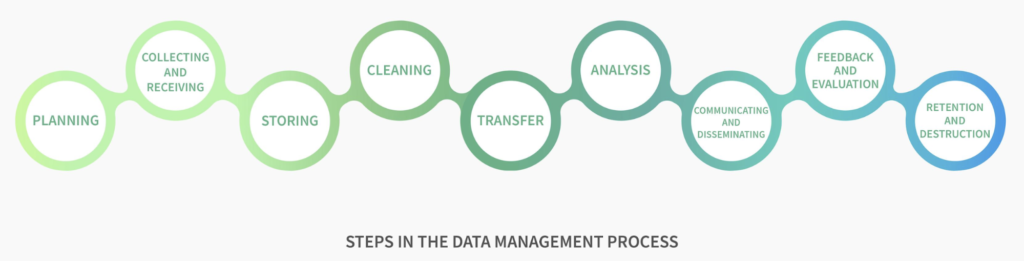

As explained in Sarah Telford’s recent blog, the Guidelines offer a set of key actions, outputs, and tools for data responsibility at each step in the data management process, from collecting and storing to disseminating and destroying. They also provide an overview of key concepts and existing guidance, introduce foundational principles for responsible data practice, and outline an accountability structure and support services to ensure uptake.

Assessing Data Sensitivity

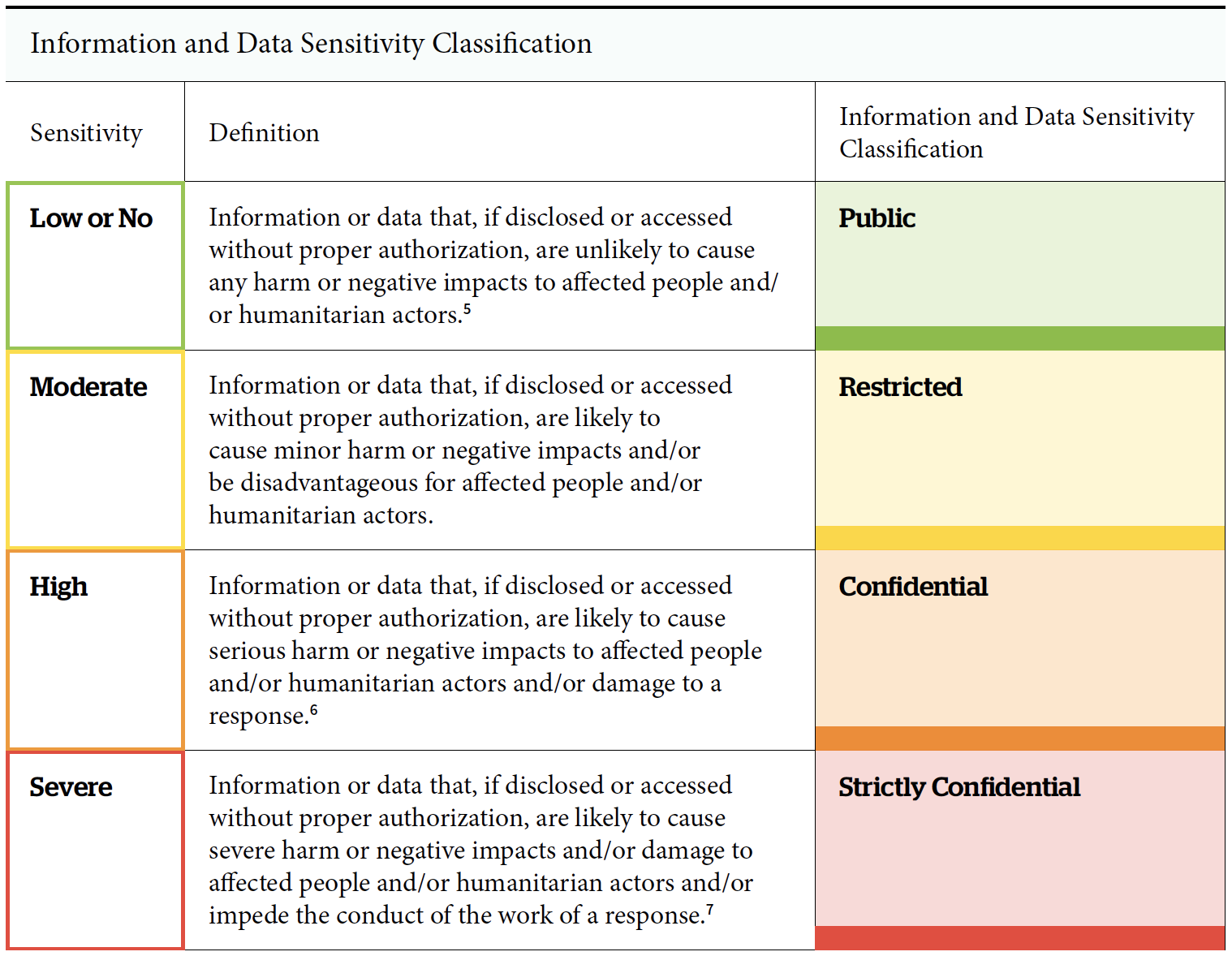

The Guidelines define sensitive data as data that, if disclosed or accessed without proper authorization, is likely to cause:

- harm (such as sanctions, discrimination, and security threats) to any person, including the source of the information or other identifiable persons or groups; or

- a negative impact on an organization’s capacity to carry out its activities or on public perceptions of that organization. Data from these different categories will have varying levels of sensitivity depending on the context.

One of the main objectives of the Guidelines is to help staff better assess and manage the sensitivity of the data they handle in different crisis contexts. Irresponsible or inappropriate processing of data in humanitarian contexts can place already vulnerable people and communities at greater risk of harm. This is of particular concern when humanitarian actors handle sensitive data. While personal data can categorically be considered sensitive, determining the risk of non-personal data is more complex.

The majority of the data that OCHA manages falls into this broader, more nebulous category of non-personal data. Examples of such data include survey results and geospatial data that can expose affected people to risk without revealing their identities.

Different forms of data can have different levels of sensitivity depending on the context. For example, locations of medical facilities in conflict settings can expose patients and staff to risk of attacks, whereas the same facility location data would likely not be considered sensitive in a natural disaster setting.

Recognizing this complexity, the Guidelines include an Information and Data Sensitivity Classification model (pictured below) to help colleagues assess and manage sensitivity in a standardized way. This classification draws on a range of existing classifications, including the Secretary-General’s Bulletin on ‘Information Sensitivity, Classification and Handling’. We expect to continue refining this framework as we test the Guidelines in different contexts.

Data Responsibility across the Data Management Process

Based on field research and the results of a data policy survey, we knew that we had to make the Guidelines practical and concrete in order to have an impact. As such, another primary objective of the Guidelines is to offer accessible, straightforward guidance and tools that staff can easily integrate into existing work processes. This is why we decided to use a holistic ‘data management process’ (pictured below) to anchor the core content.

Where relevant, the Guidelines offer templates to support different actions. For example, a template Data Responsibility Plan helps OCHA teams complete the planning step by providing a quick overview of the basic elements to get into place at the start of a data management process. The Plan is designed to help staff summarize key details such as the expected value of the exercise, the scope and volume of data required, and the risks and related mitigation measures in place.

The Guidelines also call for a set of ‘Fundamentals’ – key items to have in place in offices and sections that manage humanitarian data. This includes a Data Ecosystem Map, which provides an overview of data flows within a given response context, and an Information Sharing Protocol, which helps OCHA and its partners decide what data and information should be shared when, with whom and under which conditions.

Support Services

The Centre will offer a range of services to support the testing and initial use of the working draft Guidelines in several OCHA offices. Services range from quick introductory briefings to more intensive hands-on support, all of which is outlined on page 43.

While the entirety of the Guidelines may seem overwhelming, many of the actions proposed are already common practice within OCHA. The ‘How to use the Guidelines’ section is meant to help OCHA teams navigate the document based on the level of existing actions and guidance in their context.

Areas for Feedback

We are particularly interested in receiving feedback on the following areas of the Guidelines:

1. Assessing and managing sensitive data

- Does the sensitivity classification in the working draft of the Guidelines align with other instruments currently in use at the organizational and sector or cluster level in different response environments? If not, how could we improve alignment and what other frameworks should we be considering as we work to further refine this classification?

- Are there categories of non-personal, sensitive data that should be called out and addressed more explicitly in the Guidelines?

2. Actions, Outputs, and Tools for Data Responsibility across the Data Management Process

- For each step in the Data Management Process in the Guidelines, are there any actions or outputs missing? Do any of the actions or outputs seem redundant or unnecessary? If so, which ones?

- Are the templates included in the Guidelines useful and easy to adapt for different contexts? What could we improve in these templates to make them more practical or easy to use? What additional templates would be useful to annex?

- What additional tools would be worth referencing in the different steps of the data management process?

3. Testing and Initial Use

- What additional services could the Centre for Humanitarian Data could offer to support initial testing and use of the working draft of the Guidelines?

- Is it easy to find the information you’re looking for within the draft Guidelines? Are there any gaps in guidance, or guidance that it would make more sense to have in another section of the document?

Next Steps: Building trust through dialogue

Over the coming months, the Centre will convene a number of conversations to get feedback and develop approaches for adoption. We are holding two open community calls in March on two topics that we think need further exploration: critical incident management and data responsibility in public-private partnerships. The calls will be moderated by the Centre and feature presentations and discussion from a panel of experts representing the humanitarian community, private sector, civil society, and academia. Join our Data Policy mailing list to receive updates about these calls and other related events in the future.

In April we will hold a workshop at the Centre in The Hague with different partners active in the data responsibility space to discuss and debate different approaches to promoting data responsibility in humanitarian action. And in May, we will convene an event at Wilton Park in the UK to further examine the technological, policy, and procedural requirements for responsible data management and the mitigation of digital risk in crisis response.

If you have specific feedback on the points outlined in this blog or broader thoughts on how we could improve or extend the use of the Guidelines, we’d love to hear from you at centrehumdata@un.org.