Bill Anderson examines the potential for a down-to-earth, people-based data revolution across Africa.

On Sunday 29 March ministers from 54 African countries will gather in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia to endorse an African Data Consensus, a roadmap for the Data Revolution in Africa. Which begs the question: are we really talking about a revolution and, if so, what kind of revolution?

Talk of a data revolution has been around since the launch of the post-2015 development agenda, and the Addis high level conference is a response to a report produced by the United Nations Independent Experts Advisory Group – “A World That Counts: mobilising the data revolution for sustainable development.”

Professor Ben Kiregyera argues in his new book, “The Emerging Data Revolution in Africa”, that a number of initiatives to improve statistical capacity have been taken across Africa over the past two decades and together they constitute a revolution that is already taking place. What he describes sounds more like evolution, and when we began our joined up data work in Uganda we were sceptical of what we saw as branding rather than substance.

We have changed our thinking for two reasons.

The first struck us when we began to collect data to help address the question of why so many mothers are still dying in childbirth. For starters we needed to know how many women were in fact dying in Katakwi and Kitgum, the two rural Ugandan districts we are working in. We could then analyse the geographic distribution of these deaths and relate them to the available health services in each sub-county of the districts.

The problem is that this data literally doesn’t exist.

In Uganda the rate and incidence of maternal mortality is calculated from a Demographic and Health Survey that is conducted every five years. The most recent survey interviewed 8,674 women. This is about one in every eight hundred women of reproductive age. Data on causes of death should be available from a civil registration system. In Uganda there is an innovative new mobile vital records system recording births, but the module that is capable of recording deaths has not been commissioned due to a lack of funding. In fact few African countries currently have functional civil registration systems producing credible statistics.

Data on poverty measured as daily income is no different. This is gathered through the National Household Survey conducted every three years. The most recent survey sampled 6,896 households. This is less than one in every thousand households.

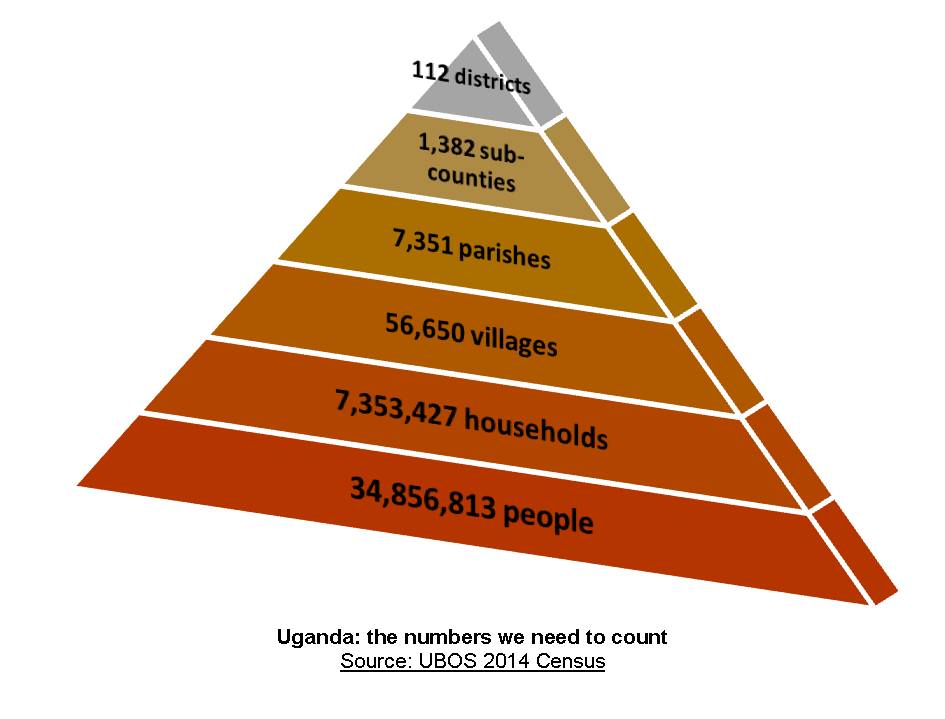

The calculations that can be made from both these surveys tell us nothing about the particular circumstances of people living in our districts. People, particularly the poor and disenfranchised, are invisible. So if we are to turn the rhetoric of ensuring that “no one is invisible” into reality, we do need a revolution. To make people count, we need to count people.

The second reason stems from the learnings we covered in our last blog. To make people count, to lift them out of poverty and provide them with better services, we don’t only need data that describes their problems. We need to quantify the resources that are available and monitor the performance of existing services. We need data on schools and clinics, on land and agriculture, on infrastructures and utilities, on budgets and expenditure. This is development data and it is needed at a local level, by district officials and community-based organisations, to drive evidence-based decision making.

The relationship between the Data Revolution and the post 2015 sustainable development goals has been the subject of much confusion. Data isn’t just needed to monitor the goals but, more importantly, to meet the goals. Take maternal mortality. We do need to know how many women are dying, but, crucially, we need data that leads to an improvement in health services; data, for example, on the resources and performance of each clinic and hospital, on drug supplies and training pipelines.

So what is so revolutionary about all this? It is the paradigm shift that is required for governments to recognise that national statistics on development must be based on disaggregated sub-national data. Sustainable development requires sustainable data. This is a down-to-earth people-based revolution.

Many thanks to Bill Anderson and Bernard Sabiti for their insights into data collection in Uganda, and the incredible potential that data holds across Africa. If you haven’t already, do read their previous articles in this feature, ‘Collecting Ugandan Data’ and ‘When Data Tells no Story.’ For further updates, be sure to follow Development Initiatives on Twitter, @devintorg.

To stay up to date with the latest Markets For Good articles and news, sign up to our newsletter here. Make sure that you are also following us on Twitter.